What does “Performance Feedback” mean to you? People describe receiving feedback from their bosses as:

• A waste of time

• Painful

• Completely off base

• A great opportunity

• Necessary

How could all of these be said about the same experience?

Many of us have experienced feedback that is off base, unfair, and poorly timed. But what if you could find value in even the most poorly delivered evaluative comments, no matter where they come from?

For years I dismissed feedback unless it was packaged in a certain way. Tell me I’m fantastic, and how, and why. I thought. Be specific!

And if you see that I could improve, you have to keep in mind how much you love me and want me to succeed. I insisted. You must reiterate your faith in me. If you don’t love me or have faith in me, your feedback is worthless here. Move along!

Not everyone would have such requirements, but because of the way I took critical feedback, they were necessary for me. I did not see myself as having a fragile ego. Rather, I saw myself as having standards. Others should be mindful about how they approach human beings with their feedback. I am happy to make sure they know the standards.

In truth, however, the way I took feedback had room for improvement. And I have been learning for many years how to process feedback so that I can get the benefit from it rather than become upset when it isn’t offered according to my rules.

In 2009, when I started facilitating workshops, my co-facilitator and I would distribute feedback forms and ask participants to tell us what their experience was like. Whenever I collected the sheets after everyone left, my attention was pulled by the section where my performance was scored against my partner’s.

This was my poison. I knew it would cause me pain, but I craved a message that I was better than my partner had been. No matter how non-competitive I might see myself in my everyday life, if you put me in a ratings race with anyone doing what I love to do, I want to win.

I typically scored higher in “preparation,” but that didn’t seem to satisfy my craving. I studied the ratings until I proved to myself that my partner had won the day in every important respect (which to me was any area where my partner had scored higher than me).

My emotional self used these ratings to treat me worse than I would ever treat anyone else. They seemed to reinforce a message: I suck. Why would anybody listen to me? I’ll never achieve anything. I should have stayed in bed.

I obsessed about it for days, during which my productivity and sociability dropped away.

So much about my experience could have improved if a miracle of time travel had allowed me to read Douglas Stone and Sheila Heen’s recently-published book, Thanks for the Feedback: The Science and Art of Receiving Feedback Well. It would have helped me to become more curious, understand and accept myself, and find a way to process feedback that didn’t hurt so much. Here is what I could have learned:

Cultivate curiosity about what people are ‘reading’ from you.

One of the first skills the authors suggest is receiving and learning from feedback “even when it is off base, unfair, poorly delivered, and, frankly, you’re not in the mood.”

What could possibly be the value in trying to learn from feedback that’s off base or unfair? Are Stone and Heen trying to suggest that you should change everything that others want you to change?

Not at all! Still, everything you do communicates something about you, and your message will have an audience.

Feedback is a chance to know what your “audience” is receiving, an opportunity to make adjustments so you can communicate your message more effectively. Is the information they are receiving (about either your content or about yourself) the information you want to convey? The only way you will ever know is by paying attention to your feedback and learning how to interpret the clues you get.

Start where you are–wired for taking feedback the way you do.

Each of us is wired to take feedback in our own particular way. According to Stone and Heen, it’s not unusual for feedback to knock you off your game if:

1. you feel it isn’t true (Truth),

2. the person delivering it is just the wrong person to say that (Relationship), or

3. the feedback threatens your understanding of who you are (Identity).

Identity is where the workshop evaluations hit me the hardest, at my sense of myself as a “really good facilitator.”

You will respond to feedback in your own signature way that is characterized by how you feel and think generally and how you process feedback in particular. I was predisposed to dismiss positive feedback and to take negative feedback hard. I was also wired to recover more slowly from those hard hits.

Others might get a big boost from positive feedback (such as “well prepared”) but aren’t so bothered by negative feedback. Their default wiring might mean they are resistant to teaching or change because they don’t take constructive critical feedback seriously enough.

By starting with a stronger understanding of your own wiring, you can develop better skills for receiving and interpreting the feedback offered to you.

Grant yourself permission to need room for improvement.

What can you do if you hate feedback that’s less than glowing? Fortunately I did discover a path that led me away from the darkness of comparison and into a healthier place. As it turns out, my strategy was right in line with the recommendations in Thanks for the Feedback.

I found a way to focus on my own numbers and compare them to previous feedback. My curiosity about how the numbers were changing developed, and I took my attention off my co-facilitators’ scores. This practice also developed my interest in how I might strengthen my skills in other categories.

The new approach helped so much. The drug-like attraction of comparing myself to others eased. My annoyance at my partners shifted to interest in my own development. Over time I saw my numbers improving relative to my own earlier scores. Even more importantly, as my facilitation skills improved, I learned to trust myself instead of craving external validation.

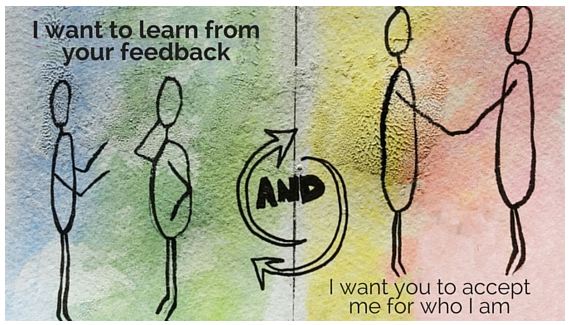

You do not have to choose between the joy of being accepted and the challenge of learning from feedback. Both are possible together. Loving yourself enough to accept feedback without fear is a wonderful practice.

For further reading about this topic, besides the already-mentioned Douglas Stone & Sheila Heen book, Thanks for the Feedback, I would recommend Brené Brown’s Daring Greatly, Carol S. Dweck’s Mindset: The New Psychology Of Success, and David Rock’s Your Brain at Work.

Bottom Line

• How open are you to feedback? If you feel pain when receiving feedback from your boss, peers, family members, or others, a new book by Douglas Stone and Sheila Heen offers suggestions. You can develop skills for receiving feedback well–even if it’s poorly delivered–by following these suggestions:

– Cultivate curiosity about what people are reading from you,

– Accept and become familiar with your default wiring for receiving feedback,

– Grant yourself permission to have room for improvement.

• How do you typically respond to feedback? Do you feel a positive or negative charge? How strong is the charge? How long does it last? If you know your typical reactions to feedback, you can predict them and even move beyond your habits.

• Try considering others’ reactions to you as information to consider. What could improve for you if you did?

• What next steps will you take to improve the way you respond to feedback?

_________________________________________________________________________

Guest Blogger Bio:

Amy Kay Watson is an ICF-certified leadership and career coach, facilitator of Coach2Lead Performance Coaching for leaders, and author of the recently published minibook, Working with Stress and Fear: Your Guide to Feeling It and Rocking The Job Anyway. Learn more at careerleadershipalignment.com and contact via amy@careerleadershipalignment.com.