Falling for the dangerous judgment errors called cognitive biases often costs you an arm and a leg. Yet such serious mistakes happen all the time in business!

For instance, one of the biggest decisions that a company can make is to merge with or acquire another company. Yet there’s an atrociously high rate of judgment errors made in M&A activity. Research shows that about 80% of M&As fail, destroying value rather than creating it.

What about another critical area, the launch of new products? We know that, unfortunately for the bottom lines of corporations, most product launches fail. Previously successful leaders who staked their reputation on the new product end up crashing and burning.

Decision-making on major projects often fails to avoid either project flops or catastrophic cost overruns. For instance, a 2014 study of IT projects found that only 16.2% succeeded in meeting the original planned resource expenditure. Of the 83.8% of projects that did not, some failed. And of the ones that did limp to the end, the average cost overrun was 189%.

What gives? Turns out that we all suffer from mental blindspots resulting from how our brain is wired, which scholars in cognitive neuroscience and behavioral economics call cognitive biases.

Fortunately, recent research in these fields shows how you can use pragmatic strategies to address these dangerous judgment errors. These techniques apply to all life areas, ranging from your career and business activities to your professional and personal relationships.

First, you need to learn the principles behind these mental blindspots to help you see reality clearly. Next, to defend yourself, along with your team and organization, from disastrous mistakes, you can use a very brief structured decision-making technique for small day-to-day decisions; a somewhat longer one for moderately important decisions; and an in-depth one for truly major or highly complex decisions.

Once you make your choice, you can use a tool to detect and remove threats and recognize and seize opportunities in implementing your decisions, and managing the resulting projects and processes. Finally, you can use another method to defeat cognitive biases and make the wisest and most profitable decisions in your long-term strategic plans.

12 Mental Skills to Defeat Unconscious Cognitive Biases

These structured decision-making and decision-implementing methods are critical to protecting you and your team from decision disasters when you have time to use them and recognize their necessity. However, you – and they – also need to develop another set of skills to develop mastery in defeating mental blindspots. These abilities will enable you to:

- Predict when you or someone else might fall for cognitive biases and prevent that problem from happening

- Recognize immediately when dangerous judgment errors are undermining the situation at hand, even if you didn’t predicted it beforehand

- Take effective steps in the moment, even when you don’t have time to use even the most brief structured decision-making process, to protect yourself or others from these biases

- Teach others how to protect themselves from mental blindspots

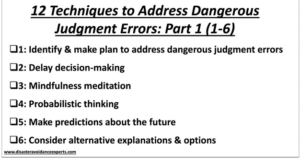

The chart below summarizes the first six techniques you can master to build the skills needed to address dangerous judgment errors. I’ll go through them one by one.

Skill 1 to Defeat Cognitive Biases: Identify and plan

First, you need to identify the various dangerous judgment errors that you are facing and make a plan to address them.

Gaining awareness of a problem is the first step to solving it. Sounds obvious, right? However, debiasing by learning about cognitive biases is trickier than it might seem. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if you could just read an article or book, or listen to a speech or podcast about these dangerous judgment errors, and voila, you’re cured!

It’s not that easy. Research demonstrates that just finding out about a cognitive bias doesn’t have much impact on addressing this problem. Of course, learning about these mental blindspots is important. However, such knowledge is only helpful in overcoming the problem when the person can evaluate the harmful impact of these dangerous judgment errors on themselves.

Understanding the stakes gets people emotionally involved and bought into solving mental blindspots. After all, our emotions determine 80-90% of our thoughts, behaviors, and decisions, making such emotional engagement critically important for the hard work of fighting cognitive biases.

What, you’re surprised that I call it “hard”? Defeating dangerous judgment errors involves changing our intuitions and gut reactions. Rewiring our habitual instincts is hard, and I mean hard.

Remember when you learned to drive a car? Maybe this ages me, but I learned to drive back in the bad old days when we didn’t have anti-lock brakes. So you had to learn to avoid slamming on the brakes when skidding on ice/snow/water and instead pump the brakes. It’s very counterintuitive and hard to do, just as it’s counterintuitive to do exercises and avoid eating that third chocolate cookie (the second is a-ok!).

Addressing cognitive biases is a critically important form of mental fitness and developing these skills is like doing exercises for your mind, just like you’re doing physical exercises to ensure physical fitness (at least 30 minutes of light exercise a day 4 times a week, right?). So protect your mental fitness well and pay careful attention to implementing these skills.

Your mental fitness is much more important than bingeing on Netflix, scrolling through Facebook, or reading yet another depressing political news story. Choose carefully what you pay attention to, as what you focus on is what you lead yourself to become. The only things in life you can control are your thoughts, behaviors, and feelings, and even those far from perfectly (otherwise nobody would eat a whole bag of potato chips, not that I ever did that, of course).

To develop these skills and rewire our automatic habits requires us to really want to do it, meaning invest strong emotions into change because we really dislike the current situation. To make that investment, it’s critical for us to have personal buy-in for transforming our intuitions. Simply learning about the cognitive bias doesn’t create such intense feelings.

However, identifying in a deep and thorough manner where that dangerous judgment error is truly hurting us – the critical pain points caused by these cognitive biases in our personal and professional activities and in the teams and organizations we lead – helps empower the strong negative emotions needed to go against our gut reactions.

Yet even that is not enough, just like it wouldn’t be enough to dislike strongly our body weight without a tangible plan to get fit through changing our diet and exercise regimen. And make no mistake, the work you and others in your team need to do to become mentally fit is just as hard as the work required to make a drastic change for the better in your physical health.

To help you truly address these dangerous judgment errors in your professional life, and in your team and organization, you need to make a plan. Make sure to answer the questions at the bottom of this article to help you figure out that plan.

Skill 2 to Defeat Cognitive Biases: Delay Decision-Making

A great deal of debiasing involves some form of shift from the autopilot to the intentional mode of thinking. After all, most, although not all, of the mental errors we tend to make come from our autopilot system.

One of the simplest ways to do so is to delay your reactions and decisions. Remember when your mom told you to count to ten when you’re angry? Well, it works to prevent harmful impulsive decisions coming from our gut reactions. So do other similar techniques to stop yourself from reacting on autopilot, especially if you tend to be impulsive (which is a weakness of mine). Instead, give yourself the time and space needed to cool down and make a more reasoned, slower response to the situation.

While counting to ten works for an immediate response situation – our intentional system takes a second or two to turn on, while the autopilot system takes only milliseconds – a more intense arousal response will require about twenty to thirty minutes to calm down. That length of time is how long it takes our sympathetic nervous system, which is the system activated in fight-flight-freeze responses, to cool down through turning on our parasympathetic nervous system, also called the rest and digest system.

Skill 3 to Defeat Cognitive Biases: Mindfulness Meditation

You won’t be surprised by this next one: mindfulness meditation. Meditation has been found by research to treat numerous problems, from pain to anxiety; now, we know it also helps us address cognitive biases.

Why? Most likely the benefit comes from a combination of delay, awareness, and focus. Meditation helps us grow more capable of resisting unhelpful intuitive impulses, being more aware of when we are going with our gut and focusing more on turning on our intentional system.

Skill 4 to Defeat Cognitive Biases: Probabilistic Thinking

Our autopilot system does not do well with numbers: it’s in essence a “yes” or “no” system, attraction or aversion, threat or opportunity. This black-and-white thinking can be solved through the intentional system approach of applying probabilistic estimates of reality. Also called Bayesian reasoning, after the creator of the Bayesian theorem Rev. Thomas Bayes, probabilistic thinking involves evaluating the probability of what reality looks like, focusing on specific and concrete images of the world. Having constructed that more rational assessment, you can update your beliefs about the world as more information becomes available.

For instance, say your business partner said something hurtful; your intuitive response is to say something mean in response. A probabilistic thinking approach involves stepping back and evaluating the relative likelihood that your business partner meant to hurt you, or that a miscommunication occurred. You would then seek further evidence to help you update your beliefs about whether your business partner meant to hurt you or not.

As an example, if she is looking at the ledger for the month and says “wow, our electric bill is so high this month” and you like the office to be warm in the winter and set the thermostat high, it’s easy to feel the comment to be an attack on you and say something hurtful in response. For instance, if she hasn’t been bringing in as much business as she usually does, a hurtful (and all too typical) response would be “well, we wouldn’t have to worry about the size of the bill if we had more money coming in.” Drama follows.

By contrast, probabilistic thinking would cause you to evaluate the likelihood of her seeking to hurt you and seek more evidence first before deciding how to respond. Thus, you might ask, “are you concerned about the electricity costs of me setting the thermostat high?” Then, she can respond, for instance saying “well, the electric bill is about two times as high as last month, and you were running the thermostat then, I think the electric company just screwed up, I’ll call them tomorrow.” Team conflict averted, thanks to probabilistic thinking. I had an exchange very much like this with my business partner and wife, Agnes Visnevkin, last winter.

My question to Agnes reflects an important aspect of probabilistic thinking: launching experiments to gain additional information. Because our gut reactions cause us to be vastly overconfident about what reality actually looks like, launching small experiments is a low-cost way to correct our evaluations of our business environment. Look for ways you can test out your theories, especially ways you can disprove them rather than confirm them, to address our tendencies to look only for information that supports our beliefs.

A key aspect of probabilistic thinking consists of using your existing knowledge about the likely shape of reality (called the base rate probability, also known as prior probability) to evaluate new evidence. In a keynote for a group of bank managers on using debiasing techniques to improve organizational performance, I spoke about using base rates to determine how to invest their time and energy into mentoring subordinates most effectively.

In a facilitated exercise, I asked them to consider how their prior mentoring impacted their subordinates. Then, I asked them to compare the qualities of their current subordinates to the prior subordinates they mentored. Finally, I asked them to consider whether their mentoring energy was invested effectively compared to the impact they could have on subordinates.

Base rates here refer to their prior experience of investing energy into mentoring and the kind of outcomes they achieved. The discussion revealed that the current behavior of bank managers did not match their estimates of employee improvement. In fact, the managers were overall spending way too much time mentoring the worst performers, perhaps 70 percent of their time on average.

Yet, the biggest impact of mentoring based on their prior experience came from improving the performance of their best performers. Informed by this evaluation of prior probabilities and how they compared to current actions, the managers determined to shift their mentoring energies and recommend that the worst performers get an outside coach, even if doing so would negatively impact their relationship with these employees.

Skill 5 to Defeat Cognitive Biases: Making Predictions

A related strategy to probabilistic thinking involves you making concrete, specific, and time-bound predictions about the future.

Let’s say you think your customers will be pleased and more likely to provide you more business of their own and referrals if you send them holiday greeting cards. Combine making predictions with experimentation by testing out this hypothesis.

Select a holiday, say Thanksgiving, and get some themed cards. Then, choose a batch of current customers that have comparable characteristics, for instance independent financial advisers who have been customers of your company between one and three years. Divide this group into two equal batches and send one batch greeting cards.

Before doing so, predict the kind of outcomes you expect to see, such as a 10 percent boost in business and a 15 percent increase in referrals over the next three months. Then, see whether your prediction turns out to be true or not. Update your beliefs – and your business processes if sending greeting cards turns out to be a good investment – based on the outcomes of the experiment.

If you’re discussing the future in a team setting, making predictions goes along splendidly with making bets. Say you and your co-founder of a tech start-up disagree about how well the new round of financing will go. Make a bet of your own money – say for $1,000 – about how angel investors will evaluate your company, for example above or below a certain amount. Doing so is a terrific way to settle disagreements and prove over time who more accurately evaluates reality. There’s something about putting down your own money which makes people step back and wake up a bit, especially if they are brimming with false confidence. The same sort of betting – perhaps for lower amounts – can be used to resolve questions in small businesses or lower levels of an organization.

Skill 6 to Defeat Cognitive Biases: Considering Alternatives

The next debiasing strategy involves considering alternative explanations and options. Say your boss is curt with you at work. Some people might take this behavior as a sign that the boss is angry with them. They would start thinking about their past performance, analyzing every aspect of it, and psych themselves out in a spiral of catastrophizing thinking. Debiasing in this case involves considering alternative explanations.

Perhaps your boss is in a bad mood because her lunch burrito didn’t agree with her. Perhaps she’s very busy, rushing to fulfill a customer’s demands, and didn’t have a chance to chat with you as she normally would. Numerous explanations exist for her behavior that do not involve the boss being angry. Combining considering the alternative with probabilistic thinking, you can follow up with your boss later in the day when she seems to have a quiet moment and observe how she interacts with you then. Then, update your beliefs based on this new interaction.

In general, try to find alternative evidence that would disconfirm in a variety of ways your intuitive gut reaction to the situation. Next, make a fuller assessment based on additional evidence. It’s crucial to decide in advance what kind of evidence would change your mind – or change the group’s decision, if you’re doing it as a team – before proceeding, so that you don’t argue afterward about what evidence counts as “good enough.”

For instance, in a group decision-making setting where two factions are at odds over which of two paths to take, you can get both to collaborate together on evaluating what kind of evidence would need to be true for either path to be the best course of action. Then, try to have both find disconfirming evidence that proves that path incorrect. That way, people won’t be fighting each other, and instead will work alongside to problem-solve the issue at hand.

Likewise, expand the range of options you’re considering through increasing your alternatives. For instance, you might be hesitant to hire someone because you’re not sure he will be a good personality fit for your team, although he has the right skills on paper. Can you bring him on as a contractor for three months and see if he is a good fit, before going through the fuller process of bringing him on the payroll?

Considering a wide range of alternative options is especially important in making substantial decisions. We have a great deal of research showing that everyone from executives to rank-and-file professionals tend to close off options too early and home in on a preferred choice. As a result, they make some real whoppers, ranging from career choices they regret to strategy decisions that cost companies many billions of dollars, say to merge an old media and new media company in a marriage intended for heaven but destined for hell (yes, I’m looking at you, AOL and Time Warner).

A very useful approach is to develop at least one and ideally two Next Best Alternatives (NBAs) to your preferred option, and then look wide and deep for reasons you should go with one of the NBAs in a significant decision. The extra time and energy you spend doing so is very much worth the cost of making an awful choice and suffering a business disaster, as many of my clients told me after starting to use this strategy compared to their prior decision-making processes that cost them dearly in the past.

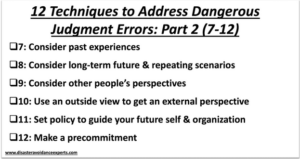

Alright, we’re done with the first six. Let’s go on to the next six, summarized in the graphic below.

Skill 7 to Defeat Cognitive Biases: Considering Past Experiences

Considering your past experiences also helps as a debiasing tactic. Do you have trouble with running late to work meetings? Are you the type of person who starts getting ready for a meeting that’s fifteen minutes away exactly fifteen minutes before a meeting?

Chronic lateness harms your relationships and reputation as well as your mental and physical well-being through constant elevated levels of cortisol, the stress hormone. Self-reflecting on how long activities have taken in the past to inform your current activities – for example, exactly when you should start preparing for a meeting to be there with 5 minutes to spare – will help your business relationships and your well-being.

Considering past experience also involves reflecting on your past successes and applying them to the present. For instance, did you have your most successful sales calls when you took the time to prepare yourself mentally to be in the most positive mindset, researched the prospect extensively, and role-played what you would say before the call? If so, then consider repeating the same strategy going forward.

Skill 8 to Defeat Cognitive Biases: Considering Future

Next, evaluate your long-term future and repeating scenarios, whether the long-term impact of a major decision or a series of repeating decisions that have a great long-term impact when combined. What happened the last time you asked your colleague to help you with a report by tomorrow? If he agreed, did he carry out his commitment, or just avoid you for the next couple of days, and then pretend that nothing happened? Is this a pattern that repeats again and again as you get increasingly aggravated about his failure?

If so, why ask him to help you in the first place? It’s not like it will make the situation any better and will only cause more conflict and grief for you both. Maybe it’s better to either have a serious conversation with him about keeping his commitments or just let it slide. This kind of evaluation of repeating scenarios can greatly improve your business relationships.

Similarly, evaluate the long-term consequences of decisions. Ask yourself three questions: what do you expect the consequences of this decision to be a day from now? A month from now? A year from now?

For instance, if you’re anxious about cold-calling prospects about a new offering, what do you think will be the result of the cold-calling a day from now? Well, the anxiety would have faded, and you might have found a couple of people who are interested in your product. In a month, you might have made a sale to one of them. In a year, that person might be one of your best clients.

Skill 9 to Defeat Cognitive Biases: Considering Other Viewpoints

You probably heard the saying “before you judge someone, walk a mile in their shoes.” Turns out this approach – meaning understanding other people’s mental models and situational context – helps debiasing greatly. We tend to underestimate by a lot the extent to which other people are different from us.

That’s why the Golden Rule, do unto others as you would have them do unto you, is trumped by what is called the Platinum Rule, do unto others as they would like to have done unto them. You’ll get much better business outcomes if you practice the debiasing strategy of considering other people’s points of view and focusing on their needs, not simply your own, in your interactions.

Skill 10 to Defeat Cognitive Biases: External Perspective

When was the last time you saw two of your colleagues arguing over something silly, perhaps lubricated by some alcohol in the evening after a conference? It happened to me a couple of days ago.

From your outside perspective on the conflict, you easily recognize that fighting over the issue at hand was not productive and even harmful. Why didn’t they see it themselves?

Because the inside view – from within a situation – blinds us to the broader context of what’s going on, leading to poor decisions that harm our relationships. To help yourself address this problem, try to look at the situation as objectively as possible by using an outside view to get an external perspective.

The quickest but least reliable method is to get a quick external perspective from yourself. Ask yourself what you would recommend a peer to do if they were in your position. You’ll often have more clarity by gaining that distance from your own gut reactions and intuitions.

However, it’s usually more effective to get an external perspective from other people, if at all possible. You can get this outside view by consulting an aggregator of external opinions: for instance, you can consult Glassdoor.com, which lists confidential reviews by employees about a company’s culture and working conditions, before accepting a job at a company. You can also speak to someone you trust and who knows your quirks, including where you’re likely to make mistakes.

It’s especially helpful, whenever possible, to get that external perspective from someone with expertise on the topic. For instance, if you are challenged by managing two teams that are constantly at loggerheads with each other, go to someone in your organization who has successfully managed intransigent teams and get her advice. If you are struggling to address persistent personnel problems, such as lack of willingness to accept new initiatives, and you have no internal resources, consider getting an external consultant or coach to help.

Skill 11 to Defeat Cognitive Biases: Setting a Policy

One of the easiest ways to address cognitive biases involves setting a policy that guides your future self or your organization. In the heat of the moment it may be hard to delay decision-making, consider alternatives, or practice the Platinum Rule. Yet if you set a policy by which you abide, especially by using a decision aid, you can protect yourself from many dangerous biases.

For example, say you’ve committed to avoid responding to professional emails that make you mad for at least thirty minutes. That’s a great policy, as it ensures you have enough time to cool down by turning on your parasympathetic nervous system through, say, stepping away from the computer and taking a brief walk outside.

It would work even better with a decision aid, such as Gmail’s “Undo Send” feature. If your autopilot system gets the better of you and you find yourself typing out an angry response email and sending it, the “Undo Send” feature allows you to unsend the email, at least for a few seconds after you hit “Send.” Trust me, that feature served me well a number of times (my default response in the saber-tooth scenario is “fight”). Other decision aids include creating checklists to consult on certain decisions or processes and making visible reminders to encourage us to be our best intentional selves.

A critical aspect of setting a policy for your future self involves fighting against the anchoring bias, our tendency to be stuck excessively on our initial predispositions. Research strongly suggests that when we try to fight our intuitions, we will tend to not go nearly as far as we should due to the anchoring bias. We need to go much further than feels comfortable to de-anchor ourselves and end up much closer to the best place to be. Don’t worry, you’re very unlikely to overshoot and go too far, according to the research. Setting a policy helps us go beyond our comfort zones.

For an organization, setting a policy is a standard matter. You can set a policy for your organization to have everyone undertake a structured decision-making process for any decision that they want to get right. Such strategies prove very effective for addressing mental blindspots. This applies to making minor daily decisions, more significant decisions, and for critical decisions, and enacting such decisions. The best way of using such techniques to protect the bottom lines of organizations involves integrating them as part of the normal order of operations for a business.

Skill 12 to Defeat Cognitive Biases: Making a Precommitment

A related strategy involves making a precommitment, specifically a public commitment, to a certain set of behaviors, with an associated accountability mechanism. For instance, a business joining the Better Business Bureau involves committing to follow a set of ethical guidelines. This public promise, along with the BBB accountability mechanism, makes us more likely to follow that set of ethics, even when our autopilot system is tempting us to take ethical shortcuts. The Pro-Truth Pledge functions similarly for a public commitment to truthfulness for individual professionals, with a similar accountability mechanism.

Both of these public commitments boost the reputation of a business or individual professional in exchange for being held accountable for one’s promise. The autopilot system’s tendency to cut corners is held in check – at least somewhat – by this commitment.

The public nature of a commitment encourages our community – the people who know about the commitment and care about helping us be our best selves – support our efforts to change our behavior.

Let’s say that you have a weakness of saying “yes” too often to requests by your colleagues and your boss is warning you that you’re spread too thin and not getting your own work done. This happened to someone I was asked to coach, and what I advised him to do – and he successfully implemented – was share about this problem with the very same colleagues who kept making requests and ask them to help him. They were highly supportive, both decreasing their requests and reminding him to avoid accepting requests from others.

In an organizational setting, a precommitment can involve committing to a certain decision or plan publicly. How many times have you seen subversive efforts to undermine plans or decisions by people who disagree with them? Frequently, such behaviors result from the lack of a transparent and thorough decision-making process where everyone had a chance to buy into the final outcome and make a clear commitment to it.

Instead, what I often see happen – when I am brought in to consult on addressing an increasingly toxic culture – are decisions and plans made by a small clique who have the political weight of power in an organization. These plans and decisions are often undermined by those who are not part of the clique and did not participate fully in the decision-making process.

When decisions and plans involve significant risk, uncertainty, and disagreements, it can really help to make a precommitment to a certain commonly-agreeable point, called a Schelling point by scholars, at which to revisit the agreement. That way, everyone can work together and pull in the same direction until the Schelling point is reached.

For instance, an organization I consulted for set a Schelling point for the launch of a new product of $14 million in sales in the first six months as the test of whether the launch plan for the new product should be reconsidered; another set a Schelling point of 12 months before evaluating the quality of a new performance evaluation process. In both cases, these precommitments protected team members from acrimonious debate of whether the product or performance evaluation process is working, as they knew there would either be a potential trigger ($14 million) or definitive date (12 months) at which to reconsider the decision.

Conclusion

It’s vital to protect yourself and those in your organization from the disasters resulting from falling for unconscious cognitive biases. You should integrate structured decision-making into all of your business systems.

However, you also need to do the hard work of developing the 12 mental skills that cognitive neuroscience and behavioral economics show effectively defeat these mental blindspots in yourself and your team. Let me be honest (no need to assume the worst, it’s not like I’m dishonest at other times, it’s just that I’m using this phrase to prepare you for bad news, ok?). These skills sound – and are – simple, but developing the mental habits to use these skills in the moment isn’t easy, since it involves changing your basic intuitions and habits. To remind yourself of these techniques, you can use this decision aid.

Remember, to rewire our intuitions requires a deep desire to achieve this transformation, because we really dislike the current situation of being vulnerable to decision disasters. I hope you make this commitment to outstanding mental fitness and join me in the wise decision maker movement.

Key Takeaways

To avoid decision disasters and defeat unconscious cognitive biases, develop the 12 critical skills that cognitive neuroscience and behavioral economics show are needed for mental fitness. —> Click to Tweet

Questions to Consider (please share your thoughts in the comments section)

- Which of these 12 skills do you think will be easiest for you to improve? Which one will be the hardest?

- How can developing the 12 skills benefit those in your organization?

- What next steps can you take to bring these skills into your team?

Image credit: Max Pixel/CC0 Public Domain

—

Article Originally published at Disaster Avoidance Experts on August 9, 2019.